Dear readers, as much as I beat the drum of Health At Every Size (HAES), I have a confession to make: I am not what most would consider “healthy.”

A Cough, a Crash, a Tangled Cluster of Symptoms

Most mornings, upon waking up, I cough. I cough and cough and cough. I feel pressure under my ribcage and a film in my throat and I cough, cough, cough until I gag. After gagging for a bit, I usually vomit a bright yellow fluid into the sink, the neon color I came to know when when I had gallstones at 18. It’s bile. And this happens every single morning.

It’s been happening for years. And, I should assure you, I’ve been to the doctor about it many times. Doctors run blood tests. My results tell them that I have an elevated bilirubin count (an inherited condition called Gilbert’s syndrome, which is benign but means that when I am overtired or stressed, the white of my eyes take on an attractive yellow hue), that my Vitamins D and B-12 counts are low, and my thyroid is “borderline,” whatever that means. The doctors are flummoxed by my symptoms and tell me it’s probably just acid reflux. One doctor recommended that I eat a handful of almonds for breakfast to combat it.

I am still paying off an endoscopy done several years ago. My husband, then my boyfriend, came with me to the hospital and sat by my side as I came out of anesthesia. The gastroenterologist approached as I was waking up, and spoke to my husband, Greg. Greg asked him if they were able to see anything. He said, “Well, she’s got a hiatal hernia, but it’s mild, and there’s bile in her esophagus and stomach.” Greg asked if anything could be done. The gastroenterologist suggested weight loss surgery. “When you’re that heavy,” he said, motioning to me, still motionless on a gurney, “there’s nowhere for the bile to go. It’s like an overstuffed suitcase.” Greg sputtered a little, and asked, “I heard you talking to another patient with a hernia a few minutes ago about a treatment for her hernia, could you do that for her?” And the gastroenterologist replied that, no, he could not, I needed to lose weight. I started to softly sob on the gurney. The gastroenterologist came over, apparently startled that I was awake, and looked at me quizzically. He asked why I was crying. I wanted to tell him, “Because you just called me an overstuffed suitcase, you asshole,” but instead I just put my head down on the pillow and wept.

I looked at the photos of my esophagus and stomach taken during the endoscopy. And there it was: the neon fluid I’d been seeing in the sink every morning, pooled in my esophagus, my stomach. I was never offered any treatment for this situation beyond weight loss surgery. It was not supposed to be there, everyone agreed. But what could be done about it? The ball was in my overstuffed court.

And the bill? It came to thousands of dollars, because the anesthesiologist the hospital brought in to put me under for the procedure was out of network and my HMO didn’t cover his services, despite the fact that I spoke with the hospital three times before my procedure to ensure that all services were in-network. So, I am still paying for privilege of taking a day off work, dragging my husband to the hospital and having that endoscopy to be compared to “an overstuffed suitcase.”

And, still, the first thing I do every single morning is cough and vomit. It’s how I greet the day. I wish I could say it’s a morning ritual I enjoy that really sets a positive tone for my day, but alas, dear readers, it is not.

Another morning ritual is that I’ll stumble out of the bathroom, looking beaten and puffy. My sweet husband will softly ask, “Are you okay?” And I’ll rasp, “Yes, I’m fine, just feeling a little sick.” And he says “okay” but I can see the concern and sympathy on his handsome face. He’s thin and fit as a fiddle, but has health issues as well. This is one of the things that connects us; we understand each other, and understand what it’s like to suffer, then put on your pants and go to work like it never happened.

I also suffer from chronic gastric symptoms. Sometimes eating a single egg can incapacitate me for days, leaving me wondering if I should just move into the bathroom full-time. And sometimes, when I eat, I can feel my hernia, I can feel food getting trapped. It feels like I’m suffocating and I can’t swallow. Some days, as I talk to coworkers and clients and put on a happy face, my chest and throat are burning from reflux, my throat is painful and scratchy from my morning ritual, and I can feel acid sloshing around in my stomach, burning my stomach lining and lurching up my throat. But I’ve become a good actor, smiling through the pain, cracking jokes. I’m always very quick with the jokes. No one will ever know you are in pain if you’re smiling and cracking jokes.

Chronic illness is exhausting. Sometimes I want nothing more to put a name on this beast, this cluster of symptoms, because knowing a monster’s name gives you power over it. But instead it hangs nameless over my life like a thick, black, acrid cloud.

I do the best I can. Eating feels like Russian roulette. Will this cause cramping? Bloating? Nausea? Will I be able to keep it down? Will I have to spend the evening on the couch after I finish this meal? It’s a never-ending game. I almost never win.

The other issue is my knees. I was in a car accident 11 years ago. My yellow Chevy Cavalier collided with a horse trailer on the driver’s side, crushing my knee against the center console. The airbag went off in a loud “BANG!” that filled my crumpled little car with smoke. After it deflated, I opened my car door and intended to ask the driver of the horse trailer if the horses were okay. I took one step on my knee and it crumbled underneath me. I fell to the ground like I had been touched by God. I saw stars. The ambulance took me to the hospital and I had an x-ray done. They said it was just soft tissue damage and sent me home with a prescription for Tylenol with codeine and a pair of crutches. They said I should heal in a few weeks.

I was able to walk without crutches in a few weeks, right on schedule, but my knee was never the same. First it was my right knee that was the problem — it cracked and popped and hurt when I stretched it out or walked up a hill or stairs. Then, the other one started to ache and pop, from nursing my damaged right knee. And then, my whole alignment was thrown off, and my hips, ankles, and back started to get in on the circus of my “healed” injury.

When I wake up, my whole body aches. I limp to the bathroom for my morning ritual. I move like the undead at first, lurching and hobbling on limbs that are deteriorating. And I loosen up as the day goes on. The aches fade into the background, elevator music in my day. Always there, a dull, constant annoyance.

I have been to doctors about this, too. They usually look at me and ask me about weight loss surgery. “Have you considered it?” I wind up to pitch them the response I’ve formed in my head, about how dangerous the surgery is, about the lack of data on long-term mortality rates and misleading data about success, about my concern that it would only make my symptoms worse, about its permanence, about my fear of being cut to pieces, about my fear of the pain, about my fear that it will just add to my tangle of symptoms, but instead I just sigh and smile. “Yes, I’ve thought about it,” I say. I’m tired. “I’ve decided it’s not right for me at this time.”

Eating for Immortality

For most of my life, I have been terrified of death. And I dieted to fend it off. “Not today, good sir,” I’d say, eating my perfectly measured and weighed bowl of plain oatmeal. “I am eating healthy and you cannot touch me!”

I counted calories, counted Points, counted macronutrients like beads on a rosary. I dieted as a fevered prayer, hoping that it would slow my body’s decline.

And so much of our behavior toward food is an act of faith. Dieters split into sects: Intermittent fasters, carrying the flame of St. Catherine of Siena and other saints who fasted to be close to god. “Clean” eaters purge the body of sin by only eating the purest and most holy foods. Proponents of the ketogenic diet forgo sugar and carbohydrates, plunging their bodies into ketosis, which some experts theorize also gave fasting saints’ bodies and breath a “sweet” odor after they expired that was used as evidence of their sainthood and incorruptibility. And weight loss surgery is penance. A pound of flesh, a bit of stomach, for the offering. Weight Watchers gather in meetings often held in churches, tithing with membership fees.

And sects of dieters are evangelists. Dieters do not worship in silence. Oh no. Wade into the comments section of any article about keto or Whole30 and see how long it takes for someone to pull up a soapbox and evangelize. “Have you heard the good word about our Lord and Savior ketosis?”

But, eventually, I realized that death comes for us all. And death does not take your vitals and run a full panel of bloodwork beforehand. Death sneaks up and snatches you when you least expect it. Cancer, a car accident, a stroke, an aneurysm, a psycho killer with an automatic rifle. My mother, the picture of health, who worked out at the gym five times per week, found out she had not one but three aneurisms that could kill her. My mother, fit and trim, walked around with three ticking time bombs in her head. BOOM! It would be so fast, she wouldn’t even know what had hit her. She had her aneurisms repaired with small metal coils, and is well.

Others around me also had brushes with death. Two coworkers with cancer — one survived, one did not. Both were “healthy,” until they were not. My grandmother, whose consumption of Shaklee vitamins (which looked like precious stones, kept in a treasure box on her kitchen counter) could only be described as religious, who was always moving, always eating like a bird, is in a memory care facility because dementia has taken her mind from her. She developed osteoporosis. She fell, broke her pelvis, and has not walked since. She also was “healthy,” until she was not.

My faith was shaken to its core.

But, like any moment of revelation, it was freeing in so many ways. I surrendered to death. Death lurks around every corner, it’s true, but there is little I can to do fend him off or prevent him from finding me. Weighing my oatmeal and counting carrot sticks will not prevent death from taking me. Losing 2lbs per week on Weight Watchers will not prevent death from taking me. These small decisions (to eat a cookie or not to eat a cookie?) no longer held life or death consequences. I decided, “Life is short. Eat the cookie, if you want to eat the cookie.”

And I felt so free. But, also, my knees still ached and popped. I still threw up in the morning. I suffered from fatigue, headaches, stomach cramps, and all the ailments that had plagued me throughout my life.

Health Looks Different for Every Body

I wondered if I was a charlatan, preaching Health At Every Size, knowing full well that my body was full of creaks and aches and uncertainty. Sometimes I still wonder, on days when doing anything beyond sitting on the couch seems impossible.

But what I know is this: health is not a fixed state. It’s an ongoing journey. It’s a journey we’ll all be traveling our whole lives, until we die. We will aim to be healthy, until we cannot.

As babies, health is simply a matter of staying alive. Did you make it to toddlerhood? Congrats, you made it. Onto the next stop, childhood, where in addition to not dying, you have to grow. Got there? Cool, now you’re a teenager, and health is growing into an adult, awkwardly, painfully. And so on until health reverts back, in old age, to simply not dying.

As long as we are alive, health is achievable. But what health means is very subjective. We all have different jobs to do, and we’re all at different stops.

For me, health means a lot of different things, and sometimes it depends on the day. Sometimes, it’s managing to wake up in the morning and not feel nauseated. Sometimes, it’s making my way up a challenging flight of stairs with minimal cracking and popping from my knees. Other days, it’s going outside and taking my dog, Cooper, for a walk, and being able to trot alongside him as he sticks his snout up in the air to catch a scent on the breeze. For me, “healthy” means eating a meal I’ve lovingly prepared, without any discomfort afterward. Sometimes it’s remembering to eat at all. And sometimes it’s giving my poor, painful legs a rest, remembering to drink water and take my vitamins, stopping work at 5 p.m., and making an effort to get 7-8 hours of sleep.

Health may look very different for others. For some, being in peak health may mean being able to climb Mount Everest. (Although, surprise, you may die there. People die trying to summit Mount Everest every year.) For others, health may involve performing rituals with diet to ward off death. And for others, it may mean remembering to take their medications so they manage their mental illnesses. Health looks different for every body.

When we adjust our concept of health to take into account the whole person, the life they have lived, the hardships they have overcome, the crosses they bear, health becomes personal. It’s not a number on a scale, or visible abdominal muscles, or being able to complete a 5k. It’s just about being the best human that you can, with the cards you were dealt, with the life that you have, and the body you have.

Chronic Illness and Weight

Illness usually has to fit a narrative to be believed. Illnesses that are not easily understood by doctors are most likely to be chalked up to a failure of character, a failure of morality. Fatness (or the medicalized term, “obesity”) is seen as the ultimate failure of character. And illness that exists within a fat body, or any marginalized body, are less likely to be believed as genuine. Our illness has a meaning, a narrative, and it is all about our moral failings. Even if our illnesses take on lives of their own, wreaking havoc on our bodies, our lives, our relationships, they will always exist in the narrative framework of our fatness.

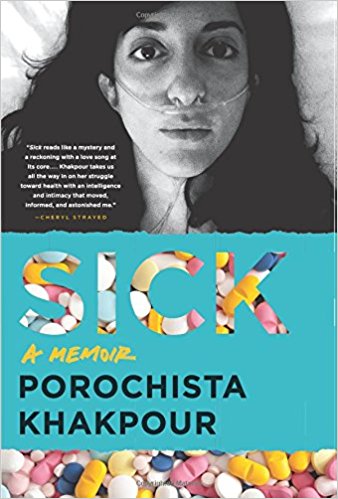

For some with chronic illness, it can be turned into a better narrative. For women who are thin, they can present themselves as they were before illness struck — beautiful, active, confident, ready to tackle the world. Their illness is a villain, striking them down, stealing their light, turning them from fair maiden into poor consumptive wretch. Porochista Khakpour’s memoir, “Sick,” gives visual representation to the beautiful consumptive narrative, featuring a photo of her, in bed, with a nasal cannula interrupting her thin, beautiful, doe-eyed face. Thin women may not be believed when they are sick. Women have suffered from multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, chronic fatigue, endometriosis, PCOS, and fibromyalgia without being believed, told it’s “all in their heads.” But these woman are, for the most part, allowed to be ill. They are given the privilege of being able to fight to have their illnesses named, to write books and make movies about their illnesses, because they are not presumed to be at fault. They get to be the heroes of their stories.

For fat people with chronic illness, it’s different. We wear the assumed cause of our illness around on our bodies, where it’s visible to everyone. It can be hard, as a person living in a fat body, to even say, “I don’t feel well.” We dread the doctor, and avoid going, because we know that we will not have our pain addressed, only the apparent cause that swells up from our bones.

I am fat, and I am chronically ill. My pain, my illness, is something I carry around with me at all times. I do not have a name for my illness, because each time I get close to finding its name, I am asked if I’ve thought about weight loss surgery. Pay your pound of flesh, please. I am afraid to speak out loud about my illness, my pain, because those around me have already assumed the cause. But I don’t know the cause. I don’t know its name. And I have begun to make peace with the idea that I may never find out. I will carry it on my back until I die.

And sometimes, just to survive in this world in a fat body, I find that I must appease the peanut gallery. Yes, I eat fruits and vegetables, all the time. Yes, I have tried to lose weight. Yes, I have thought about weight loss surgery. Yes, I exercise. Yes, I understand how nutrition works. Yes, I have heard of this diet. Yes, I have tried.

Sometimes I think about paying the pound of flesh, just so I can be heard. I think, if I finally submit to weight loss surgery, the prescription for all of my ailments, I can finally say, “See? Still sick.” And perhaps then, someone will take action beyond prescribing almonds and weight loss.

This is why weight loss surgery is such a complicated issue to address. For many fat people, it’s not about vanity, or wanting to be thin. It’s about survival. It’s about gaining the privilege of being heard. It’s about being able to say, “I don’t feel good,” without having a chorus of people saying, “Of course you don’t feel good, you’re fat.” It’s about not being at fault for every ache, pain, and sickness.

I’ve decided it’s too much of a gamble for me. I live with the pain of being fat and ill each day, and it’s a burden I can bear. I can even bear it with a smile. Undergoing surgery, being cut to pieces, paying my pound of flesh, for the privilege of being seen and heard, is not a fair price to pay for me.

Proving Your Worth

What I lack is the beautiful “before” picture that demonstrates just how much my various symptoms have dragged me down. And my “after” picture isn’t so great either.

When I first learned about HAES, my goal was to prove that I can meet the universal standard of “healthy” — perfect bloodwork, perfect blood pressure, perfect cholesterol. I felt defensive. I wanted to run 5ks and do fat yoga and be one of those badass fat people breaking boundaries and busting stereotypes.

But what it took some time to realize was this: fat people are at a severe disadvantage when it comes to health because of the bias we encounter from the medical establishment. So, much like body positivity puts the onus on people in marginalized bodies to love themselves instead of putting pressure on the systems that marginalize and oppress their bodies, this approach to Health At Every Size can put the onus on fat people to be healthy without acknowledging that fat people face significant challenges to being “healthy” that have nothing to do with their weight and everything to do with bias and discrimination.

Fat people are often treated poorly by medical professionals.

Medical professionals, doctors, nurses, are often hesitant to even touch fat people. Sometimes their disgust cannot be hidden under a veneer of professionalism. (Example: Recently I went to an urgent care clinic for a neck injury. The nurse’s assistant who took my vitals did not take my blood pressure and instead put a made-up number into my patient record. The doctor who saw me gave me a handout about hypertension. I was confused and told him my blood pressure was never taken. He made the nurse’s assistant come back in and take my BP; she fumbled with the Regular-size cuff, annoyed. I instructed her to get a thigh cuff. She looked confused and started to put the thigh cuff around my thigh. I informed her she should put the larger thigh cuff around my arm. Duh. She took my BP. It was normal. I had been diagnosed with hypertension in my patient record because this nurse’s assistant did not want to get close enough to take my BP.)

Fat people have their symptoms dismissed or overlooked because medical professionals cannot (or will not) see beyond their body size. Their weight becomes the catch-all diagnosis for every ailment under the sun. (Example: I went to see a nurse practitioner about a sinus infection and left with a recommendation for weight loss surgery. This is an absolutely true story.)

We fear going to the doctor, because we fear being treated poorly, having our symptoms dismissed, and not receiving competent, compassionate medical care due to our weight. Sometimes this means by the time we do see a doctor, our symptoms are worse than the were initially, and have become unbearable.

And sometimes our weight is a symptom. Sometimes we have lost weight, but are lauded by medical professionals for our good work instead of looking closer to see why a patient may have lost weight unintentionally. Sometimes we have gained weight, but are chided for our lack of self-control or poor diet or sedentary lifestyle instead of looking for other causes.

And this doesn’t even begin to cover the societal forces that put fat people at a disadvantage when it comes to our health. The fact that it can be harder for us to be hired, and when we are hired, we will probably be paid less. (Double that if you’re brown or a woman or disabled or trans or non-straight, and triple that if you’re all of the above.) This leads us to be more likely to encounter issues with insurance coverage (which is tied to employment in the U.S.) and more likely to live in poverty (which leads to problems with food affordability).

Good activists, like Ragen Chastain, and Dr. Linda Bacon, and Lindy West, and Jes Baker, know these things and fight to for us … the people who can’t run marathons because of illness or injury, the people who can’t access competent, compassionate healthcare, the people on the margins who simply want access to “health.” They fight for health to be intersectional.

The problem is that it can be hard for doctors and the general public to understand. And, well, it can be hard for us to understand. Other fat people are out there, running marathons, dancing, doing yoga … why can’t we? Are we bad fatties? We feel the need to defend ourselves. We feed into healthism. We strive to provide answers, to fend off questions about whether our bodies are worthy of being fought for, whether our asshole doctors are right and we really did bring this all on ourselves. We want to be good fatties, who can demonstrate that you really can be healthy at every size.

I don’t claim to know the answers. I’m working on making peace with Health At Every Size and living in a body that feels sick and tired more days than not. I’m working on how to exercise with a bad knee, bad back, and all my aches and pains. I’m working on how to eat for my health, and what my relationship to “health” even is, and how to define health for my own body and my own life. I’m working to divorce my worth from a fixed definition of “health.”

But I’m just admitting everything here, dear readers, because I want you to know that’s it’s okay not to have this stuff figured out. It’s okay to feel sick. It’s okay to be chronically ill, it’s not your fault. It’s okay to be in pain, or be tired. It’s okay to fight to have your pain and illness named, and it’s also okay to just do the best you can to live with it. It’s okay if you can’t run marathons or struggle to walk up a flight of stairs. It’s okay to be on a journey to find out what all of this shit means to you and your life.

All we can do is our best, and support each other, and share what we learn. And practice compassion, always, not just with each other, but also ourselves. That last part is hard, but I’m getting there.

I just loved reading this. So much raw hearted truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! It means a lot. ❤

LikeLike

Just discovered your blog through a Linda Bacon tweet. Beautifully written. I can relate to every word. Thanks so much for putting a voice to feelings I’ve had for decades.

LikeLike